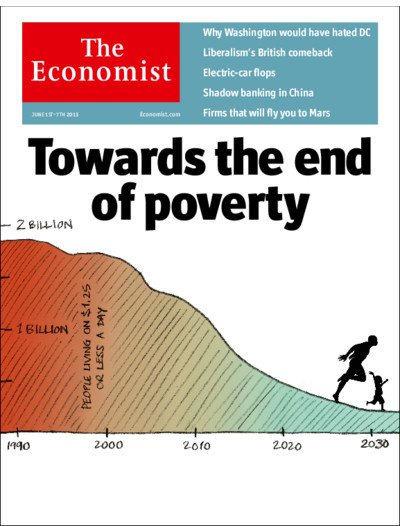

At the end of last year, quoting an article by The Spectator, I had reported several data from reliable sources leading to a surprising conclusion: “2012 was the best year ever.”

This wasn’t, six months ago, a vague exercise in irrelevant “optimism.” And it isn’t so now with an analysis of worldwide poverty trends published by The Economist on June 1st 2013.

Copyright © The Economist 2013This is, indeed, good news – on a large, worldwide scale. But much more remains to be done. Problems remain very serious and complex. It would be dangerously stupid to assume that they can all be solved by just following the trend or doing “more of the same”.

On the other hand, experience is a vital resource. The outcome so far proves that substantial results can be accomplished – and therefore it makes sense to be seriously committed in the achievement of further improvements. While continually learning, from observation and practice, which are the most effective tools, assets and methods.

We need also to remember that all statistics always need to be examined critically, to understand their limitations and real meaning and to avoid simplistic confusion. For instance, in this case, the standard measurement is “per capita income” – i.e. “gross national product” divided by the number of inhabitants. By general consensus in the UN and other international organizations, the “extreme poverty” threshold is set at 1.25 dollars a day

Some sort of roughly equalized criterion on a worldwide scale is useful for a global trend analysis – which, as such, is meaningful. But it’s far from being precise or homogeneous.

For instance “gross national product” (and therefore income) is based on monetary exchange. In agricultural economies the survival of people and families is largely based on “self-consumption”. Food that they grow, not buy, as well as self-production of other goods (including tools and shelter). When farmers become factory workers or otherwise are paid in money (as is happening in “developing countries”) with the loss of traditional land resources they can fall into dismal poverty even with much higher income than 1.25 dollars a day.

This is how it’s explained by The Economist. «Nobody in the developed world comes remotely close to the poverty level that $1.25 a day represents. America’s poverty line is $63 a day for a family of four. In the richer parts of the emerging world $4 a day is the poverty barrier. But poverty’s scourge is fiercest below $1.25 (the average of the 15 poorest countries’ own poverty lines in 2005, adjusted for differences in purchasing power): people below that level live lives that are poor, nasty, brutish and short. They lack not just education, health care, proper clothing and shelter – which most people in most of the world take for granted – but even enough food for physical and mental health. Raising people above that level of wretchedness is not a sufficient ambition for a prosperous planet, but it is a necessary one.»

Another problem is that the concept of “average” person or family is seriously questionable. In many parts of the world very few people own most of the wealth while the majority is painfully below average.

To make things even more complicated there is the current degeneration in “traditionally rich” countries. Pathological financial dementia has caused an absurd “crisis” in which not ownly overall income decreases, but a growing share is concentrated in ever fewer hands while most of the people are losing. This is the opposite of any healthy economic and social development.

In spite of all the necessary precautions in the evaluation of data, the broad analyses of “decreasing poverty” are remarkably meaningful and relevant. This is how the Economist article begins, quoting an outstandingly clear perception of the worldwide perspective 64 years ago.

«In his inaugural address in 1949 Harry Truman said that “more than half the people in the world are living in conditions approaching misery. For the first time in history, humanity possesses the knowledge and skill to relieve the suffering of those people.” It has taken much longer than Truman hoped, but the world has lately been making extraordinary progress in lifting people out of extreme poverty. Between 1990 and 2010, their number fell by half as a share of the total population in developing countries, from 43% to 21% – a reduction of almost 1 billion people.»

«Now the world has a serious chance to redeem Truman’s pledge to lift the least fortunate. Of the 7 billion people alive on the planet, 1.1 billion subsist below the internationally accepted extreme-poverty line of $1.25 a day. Starting this week and continuing over the next year or so, the UN’s usual Who’s Who of politicians and officials from governments and international agencies will meet to draw up a new list of targets to replace the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which were set in September 2000 and expire in 2015. Governments should adopt as their main new goal the aim of reducing by another billion the number of people in extreme poverty by 2030.»

So it should decrease from nearly two billion in 1990 to approximately 500 million forty years later. It would still be a tragically enormous number, but extraordinarily smaller (as a percentage of population) than it has ever been in all human history.

It would be useful (though it isn’t easy) to gain a better undertstanding of how and why the situation has been evolving. There are considerable differences in the evaluation of changes so far. The most important of the “Millennium Development Goals” was to to halve the number of people in extreme poverty by 2015. According to data published by the World Bank on February 29, 2012 (and reported by The Spectator in December) the goal was reached seven years earlier, in 2008. The Economist appears to be estimating slower evolution – but even so expects the task to be achieved before 2015.

Overall data are necessarily simplistic. Reality, everywhere, is a mixture of turbulent complexities, in which some things are getting better while other are deteriorating. Encouraging improvement requires obstinate clarity of objectives combined with flexibility in facing unexpected problems and also seizing unpredictable opportunities.

Making people poor and unhappy in “rich” countries doesn’t help to reduce poverty elsewhere. Conversely, exploitation of the poor is a benefit only for selfish, nearsighted oligarchies, not for the majority of people living in less unfortunate environments.

The problem, everywhere, is too much money (and power) held by egoistic and egotistic minorities. Reversing this obnoxious trend isn’t only a matter of ethics, empathy and solidarity. It’s a practical, and increasingly urgent, need for the survival of our species – and the whole environment.

There is a crucial change at this time, compared to all previous history. Regardless of geography, the complex interaction of different cultures and economies is closer, and faster, than it has ever been. This, if properly understood, offers considerable opportunities for improvement. But it also causes a dangerous multiplication of turbulence, unhappiness, conflict, oppression, unfairness, cruelty and violence.

I am intrigued by the unusual tone of voice in the Economist’s reporting of the poverty decline. Usually strict and sober, more inclined to criticism than applause, suddenly using (or quoting) expressions such as «astonishing achievement», «the world’s next great leap forward», «historic opportunity», «a unique sweet spot» «the end of poverty», «eradicate poverty», «poverty not always with us» – and more of the same sort.

Of course this isn’t vague enthusiasm or naïve optimism. It’s a warm touch of sensible emotion for the pleasant fact that, in this case, humanity as a whole isn’t being stupid. More importantly, it’s a task and a challenge: a huge opportunity that the whole world can’t afford to miss.

This is the biggest of its kind, but not the only one. While many serious problems and distressing situations are going from bad to worse, in the general turmoil there are also fertile improvements that open possibilities worth understanding and cultivating.

We need to keep our eyes open for what is “possible”. A development that, per se, doesn’t lead to any straightforward solution can open a variety of different perspectives worth exploring. Turbulence, scary as a whole, often contains unexpected hints for improvement.

In the world as we know it, it’s impossible to eliminate poverty totally and forever. But it isn’t necessary. If and when it’s reduced to a much smaller size, it becomes easier to rescue out of their misery those who can’t do so with their own resources.

The change that we are achieving, for the first time in human history, is truly very important. But reducing the number of people below the extreme threshold isn’t the end of poverty. And raising “average” income isn’t enough. The yardstick must be the condition of the least privileged. Where and when too much wealth is owned by too few, the misery of he poor is even worse.

Anyhow, this can’t be only a matter of money. It is necessary to consider also freedom, health, knowledge, education, environment and culture. It isn’t easy to define and measure “quality of life”, but it’s the most important value.

Even with all the doubts and complications, the achievement of the first MDG worldwide objective is, indeed, good news. Let’s sit back and relax, if only for a few minutes, with the comforting evidence that humanity isn’t totally stupid. But the most important and durable lesson, in spite of all the bad news, is that improvement is “possible”. We need to keep our eyes open for underestimated, unexpected or overlooked opportunities.